Our humble home in Caniçal clung to the hillside like a stubborn weed. The wind slipped in through the windows uninvited, and when it rained, droplets danced directly onto the worn stone slabs of the floor, marking them like aged skin.

Winner of The Letter Review Prize for Short Fiction

The Weight of Salt

I was born in a roofless house, that winter when I stepped into the world. My mother used to say it was the stars that first blessed me—not the priest at my baptism, nor the civil servant with his stiff moustache and trembling hand, formalizing the required bureaucracy. And after the stars, it was the cold and the roar of the sea that welcomed me, as if to prepare me for what lay ahead.

Our humble home in Caniçal clung to the hillside like a stubborn weed. The wind slipped in through the windows uninvited, and when it rained, droplets danced directly onto the worn stone slabs of the floor, marking them like aged skin.

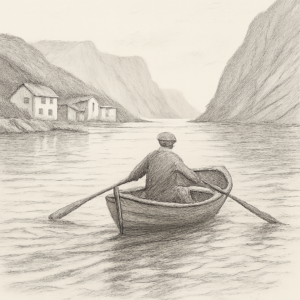

My father died the year I turned three, swallowed by the sea like too many Moreira men before him. He left a meager legacy: a net patched more times than our clothes and a small boat no one dared sell – until necessity left us no choice.

My mother never remarried. She said she’d married the sea once, and that its betrayal was enough for a lifetime. She dressed in black on the day of the funeral and never wore another color again.

She was a woman of few words, and most of them tasted of bile. Her silence became the weight I learned to carry in my chest. By seven, I could gut fish blindfolded. By ten, I knew by heart the price of every item in the modest basket I fetched weekly from Mr. Ferraz’s shop. And by fifteen, I was no longer fooled by the stench of depravity hidden behind a tourist’s smile. I never learned, however, how to dream in color. I lived and fell asleep wrapped in the grey of crashing waves and the rust-red of the cliffs where goats defied gravity.

Yes, we were poor – but not alone in it. On the island, people said “God willing” as if misfortune were a blessing already destined for us. I never saw meat at home, but I knew countless ways to cook our potatoes. When there was no milk, we drank water and blessed the chance to fast. But it wasn’t just hunger that made me leaner with each passing year. It was saudade – a word I didn’t yet know how to explain.

My mother cleaned hotel rooms for thirty years, her knees hard as driftwood. She used to say that if we stayed quiet enough, we could fit our dignity in our pocket. So I learned to walk lightly, speak little, and apologize even when I wasn’t wrong.

School was a place I went in the mornings, after doing chores at home and before another round of sun-drying gaiado. The teachers were kind, in that distant way of those unsure whether it’s worth investing their time. I wasn’t smart, at least not in the way school measured. I failed math the same year my mother lost her job. They replaced her with a machine that didn’t need rest or breaks. That night, I found her on the balcony, staring out at the sea. There was a message on her face I could never decipher.

“There are places,” she whispered, “where the sea is just decoration.”

I didn’t understand. So I kept gutting fish.

At seventeen, I met Tomás. His shoes were too clean for this part of the island, and his eyes trembled before the truth. He came from Funchal with a guitar and the idea that the world could be rewritten, chord by chord. I distrusted him from the start. His hands were soft. His shirts, holeless. But he listened when I spoke – and I guess that was enough.

We kissed once behind the chapel and I swear the stones beneath us softened. He said I should sing with him, that my voice sounded like the earth waking up. I laughed in his face. But when he left, I couldn’t stop dreaming about the stage he’d promised me.

For a while, he sent postcards. Then he stopped.

At twenty-two, I boarded a plane for the first time. I worked as a cleaner in Jersey, then in Luxembourg. I sent money home and received silence in return. My mother never answered my letters. But once, the neighbor wrote to say she still went to the market every Sunday, just in case I showed up unannounced.

I worked and worked and worked. In hotels, then kitchens, later hospitals. I became skilled at vanishing into walls. Some nights, I’d lie in bed with foreign tongues buzzing in my ear like an incomprehensible hum. My hands, once calloused from scales, now trembled over stainless steel cutlery. I met men who saw me as a curiosity, a momentary warmth. I let some in. None stayed.

One day, I woke up and the mirror refused to show me anything but my mother’s face.

I returned to Madeira the year I turned forty. My mother was dead. They said she had fallen while weeding, hitting her head on a stone I had known since girlhood. I found the house just as I’d left it: frugal, clean, silent. The bed still made. Three of my letters unopened on the shelf.

That night, I walked barefoot into the darkness toward the sea. I thought of Tomás, the postcards, the songs I never sang. The wind smelled of old rope, dried gaiado, and broken promises. I whispered to the sea, “Are you still hungry?” – and waited for an answer.

None came.

Now I am fifty-three. I work at a museum that was once a whale-processing factory. Tourists come to admire the bones of creatures they never knew we hunted. I explain how the blood was drained through the floor grates. I point to ancient harpoons. I say, “This is history.” What I don’t say is that we were always trying to gut something larger than ourselves – poverty, grief, fate.

Sometimes children visit the museum. They stare wide-eyed at the skeletons and ask if whales used to sing. I tell them yes. I lie, because someone must. Now and then, I catch my reflection in the glass cases. I still walk lightly. I still gut things, but now it’s meaning I carve out of silence. I haven’t sung in years, but on Sundays, when the wind curls just right through the trees, I hum a melody Tomás once taught me. I no longer remember the lyrics, but I remember the promise of a life greater than the island.

Maybe that’s what dignity is: not winning, not even surviving – but singing to the sea that swallowed your father, walking on a ground that never gave you rest, and still, planting something. Even if it’s only salt.

Alves dos Santos has been described as a traveler of the soul, an explorer of human stories and uncharted realms. In his words, we find the beauty of an essence in constant ferment—a blend of pure air and volcanic undertones—but above all, the portrait of a man who lives in harmony with discovery, truth, and, most of all, life.